Dinosaurs in Ancient Egypt?

According to the fossil record, the science of paleontology, and old-earth creationism websites (Zweerink), dinosaurs died out long before humans appeared on earth. But some internet sites and amateur researchers claim that there is proof of human-dinosaur contact in ancient Egyptian texts. Specifically, the argument is made that one particular hieroglyph is in fact a dinosaur of the ocean, a plesiosaur. If this is true, then Egyptians at the very least knew what living dinosaurs looked like and perhaps plesiosaurs lived contemporaneously with humans.

Dinosaurs in Ancient Egypt? A Plesiosaur Hieroglyph?

The consensus among paleontologists is that plesiosaurs lived in the Mesozoic era, roughly 65-200 million years ago. Plesiosaurs were among the first fossil marine reptiles discovered by modern scientists (Figure 1). They were identified as a specific genus in 1821. Their appearance is familiar to anyone interested in dinosaurs (or the Loch Ness monster as depicted In Figure 2):

Figure 1

Figure 1

Figure 2

Figure 2

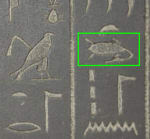

Figure 3

Figure 3

The hieroglyph that allegedly depicts a plesiosaur is pictured inside the green square in Figure 3. It’s easy to see how, if one already had the image of a plesiosaur in mind, this hieroglyph could be interpreted as the Mesozoic marine reptile. But ultimately, the test of whether this identification is coherent is discerning how Egyptians themselves conceived the hieroglyphic sign, not what modern people might be thinking.

Fortunately, determining how the Egyptians would have interpreted this sign is quite easy. This particular hieroglyph is found frequently—not merely in texts, but in Egyptian art. More specifically, this hieroglyph appears commonly in scenes involving dining and food offerings. That might sound very odd, especially if your preconception of the hieroglyph involves a marine dinosaur. But once you realize what the hieroglyph actually is, the Egyptian use of the symbol is perfectly reasonable and coherent.

Dinosaurs in Ancient Egypt? A Goose, not a Plesiosaur

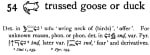

The “plesiosaur” is actually a goose—a dead goose being prepped for cooking. One of the earliest (and best) Egyptian grammars in English is that of Sir Alan Gardiner. Gardiner’s massive grammar includes a sign list with hieroglyphs grouped by an alpha-numeric system. The numbering is assigned according to Gardiner’s grouping of signs by type (e.g., humans, birds, deities). The sign in question is G54 in Gardiner’s list (G is the bird category, this is #54 in that category). Gardiner explains the sign in an appendix (Figure 4):

Figure 4

Figure 4

Gardiner’s brief entry notes the phonetic sounds associated in Egyptian with the sign and (importantly for our discussion) that it is used (by the native ancient Egyptian scribes) as a determinative (“Det.”). In Egyptian grammar, determinatives are signs that are used to classify words. In this case, this sign classifies the verb wšn which means “to wring the neck of (birds)” or “to offer” (as in a food offering).

Here’s an example of the hieroglyph in a long hieroglyphic inscription (Figure 5) now in the Louvre with a close-up (Figure 6):

Figure 5

Figure 5

Figure 6

Figure 6

Egyptian art and objects for everyday use validate the association of this sign with food offerings and, therefore, the fact that it depicts a goose. Here’s the backside of a carved Egyptian wooden spoon (Figure 7) with the usable side below it (Figure 8):

Figure 7

Figure 7

Figure 8

Figure 8

The shape of the object is identical to the familiar glyph, save the orientation of the goose and some fine detailing.

In this Egyptian offering scene, our goose is about to be cooked (Figure 9):

Figure 9

Figure 9

Examples like these are easily obtained from Egyptian reliefs and texts. We do not have a plesiosaur in Egyptian hieroglyphs.

Resources:

“Dinosaurs in Ancient Egyptian Hieroglyphs – Explained,” MDW-NTR blog (2013)

Gardiner, Alan Henderson. Egyptian Grammar: Being an Introduction to the Study of Hieroglyphs (Published on behalf of the Griffith Institute, Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, by Oxford University Press, 1950)

Patrick F. Houlihan and Steven M. Goodman, The Birds of Ancient Egypt (American University in Cairo Press, 1988)

Salima Ikram, “Meat Processing,” pp. 656-672 in Ancient Egyptian Materials and Technology (ed. Paul T. Nicholson and Ian Shaw; Cambridge University Press, 2000)

Jeff Zweerink, “RTB’s Position on Dinosaurs,” (2011)

What is your response?