The Lost City of Atlantis

The lost city of Atlantis is one of the most enduring mysteries in human history. Its status as history or myth has been debated for two thousand years. The debate persists even today, with alleged evidence turning up via sonar in the Canary Islands, Rio de Janeiro, off the coast of Spain, and Cuba.

Obviously, all these claims cannot be true, and none of them may be accurate. When one adds other proposes sites from both antiquity and the modern era, the mystery of Atlantis quickly becomes an intellectual quagmire.

The subject of Atlantis gets even more complicated when we realize that there’s a definitional problem at the outset. “Atlantis” means different things to different people. That’s part of the reason why there have been so many candidates for its location. The different “Atlantises” can be broken down as follows.

The Lost City of Atlantis: Plato’s Atlantis

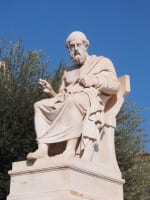

Figure 1

Figure 1

Plato (Figure 1) was a famous Greek philosopher from Athens who lived ca. 427–347 BC. Some things he wrote in his dialogs Timaeus and Critias gave birth to the Atlantis legend. As the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (SEP) notes,

In the Timaeus Plato presents an elaborately wrought account of the formation of the universe and an explanation of its impressive order and beauty. The universe, he proposes, is the product of rational, purposive, and beneficent agency. . . . The opening conversation (17a1–27d4) introduces the characters—Socrates, Timaeus, Critias and Hermocrates—and suggests that the latter three would contribute to a reply to Socrates’ speech allegedly given on the previous day. . . . This reply would start with an account of the creation of the universe down to the creation of human beings and, in a second step, show an ideal society in motion. Critias is meant to provide the second step with his account of a war between ancient Athens and Atlantis. (Plato’s Timaeus, SEP)

About Atlantis Critias reports (i.e., Plato writes):

Many great and wonderful deeds are recorded of your state in our histories. But one of them exceeds all the rest in greatness and valour. For these histories tell of a mighty power which unprovoked made an expedition against the whole of Europe and Asia, and to which your city put an end. This power came forth out of the Atlantic Ocean, for in those days the Atlantic was navigable; and there was an island situated in front of the straits which are by you called the Pillars of Heracles; the island was larger than Libya and Asia put together, and was the way to other islands, and from these you might pass to the whole of the opposite continent which surrounded the true ocean; for this sea which is within the Straits of Heracles is only a harbour, having a narrow entrance, but that other is a real sea, and the surrounding land may be most truly called a boundless continent. Now in this island of Atlantis there was a great and wonderful empire which had rule over the whole island and several others, and over parts of the continent, and, furthermore, the men of Atlantis had subjected the parts of Libya within the columns of Heracles as far as Egypt, and of Europe as far as Tyrrhenia. This vast power, gathered into one, endeavoured to subdue at a blow our country and yours and the whole of the region within the straits; and then, Solon, your country shone forth, in the excellence of her virtue and strength, among all mankind. She was pre-eminent in courage and military skill, and was the leader of the Hellenes. And when the rest fell off from her, being compelled to stand alone, after having undergone the very extremity of danger, she defeated and triumphed over the invaders, and preserved from slavery those who were not yet subjugated, and generously liberated all the rest of us who dwell within the pillars. But afterwards there occurred violent earthquakes and floods; and in a single day and night of misfortune all your warlike men in a body sank into the earth, and the island of Atlantis in like manner disappeared in the depths of the sea. For which reason the sea in those parts is impassable and impenetrable, because there is a shoal of mud in the way; and this was caused by the subsidence of the island.

Plato went into more detail about Atlantis in his ensuing dialog, Critias:

Let me begin by observing first of all, that nine thousand was the sum of years which had elapsed since the war which was said to have taken place between those who dwelt outside the Pillars of Heracles and all who dwelt within them; this war I am going to describe. Of the combatants on the one side, the city of Athens was reported to have been the leader and to have fought out the war; the combatants on the other side were commanded by the kings of Atlantis, which, as was saying, was an island greater in extent than Libya and Asia, and when afterwards sunk by an earthquake, became an impassable barrier of mud to voyagers sailing from hence to any part of the ocean. The progress of the history will unfold the various nations of barbarians and families of Hellenes which then existed, as they successively appear on the scene; but I must describe first of all Athenians of that day, and their enemies who fought with them, and then the respective powers and governments of the two kingdoms. Let us give the precedence to Athens. . . .

In this mountain there dwelt one of the earth born primeval men of that country, whose name was Evenor, and he had a wife named Leucippe, and they had an only daughter who was called Cleito. The maiden had already reached womanhood, when her father and mother died; Poseidon fell in love with her and had intercourse with her, and breaking the ground, inclosed the hill in which she dwelt all round, making alternate zones of sea and land larger and smaller, encircling one another; there were two of land and three of water, which he turned as with a lathe, each having its circumference equidistant every way from the centre, so that no man could get to the island, for ships and voyages were not as yet. He himself, being a god, found no difficulty in making special arrangements for the centre island, bringing up two springs of water from beneath the earth, one of warm water and the other of cold, and making every variety of food to spring up abundantly from the soil. He also begat and brought up five pairs of twin male children; and dividing the island of Atlantis into ten portions, he gave to the first-born of the eldest pair his mother's dwelling and the surrounding allotment, which was the largest and best, and made him king over the rest; the others he made princes, and gave them rule over many men, and a large territory. . . .

The Atlantis of Plato is the Atlantis most people have in mind when a report surfaces about an underwater city coming to light via modern technology. But we can see by Plato’s writings that Atlantis was more than a city. Historian Ronald Fritze observes:

Plato tells his readers that Atlantis is an island located just outside the straits of Gibraltar, the modern name for the ancient Pillars of Hercules. Atlantis is not just any island, but a very large land, larger than Sicily or Crete or Cyprus, which would have been the largest islands familiar to Plato and his contemporaries. In fact, Plato states that Altantis was bigger than Libya and Asia combined. Just what he meant by this comparison is unclear. Some scholars suggest that Plato was referring to two of the three continents known to the ancient Greeks: Libya (Saharan Africa) and Asia (the Middle East and India). If so, Atlantis was a rather large continent not merely an island. Plato, however, never refers to Atlantis as a continent so he may have been using a more limited definition of the geographical terms Libya and Asia. The ancient Greeks commonly referred to the region of North Africa between Egypt and Cyrene as Libya. They also sometimes called the area knowns as Asia Minor or modern Turkey by the shorter name of Asia. Taken together, the combination of these two regions would not amount to a continent-sized land mass, but it would constitute an island far larger even than Sicily, the largest island in the Mediterranean Sea. (Fritze, 23).

In addition to its own enormous size, the Atlantean empire of Plato subsumed other islands in the Atlantic Ocean and controlled the western basin of the Mediterranean. While there is nothing in Plato’s account that is atypical of its time period (the Bronze Age), it was immense. Plato of course credits its size and wealth to the gods. By way of summary, then, Plato’s Atlantis was a very large island in the Atlantic Ocean, a fantastically wealthy Bronze Age empire reaching well into the Mediterranean. At about 9400 BC the Atlanteans fought a war of conquest with Athens and lost. It was destroyed by earthquakes and floods.

Is there any evidence for this besides Plato’s writings? The answer is no, in terms of the name of the city. In that regard, though other ancient writers referenced what Plato said, there are no ancient independent sources that confirm the reality of Plato’s Atlantis. However, there are references prior to Plato (Homer, Hesiod, Pindar, and Hellanicus) that mention a “sacred circular entity somewhere West of Gibraltar” (Papamarinopoulos, 2008).

The balance of ancient writers considered Atlantis a fiction. Aristotle, Plato’s most famous student, thought the story was a myth. Pliny and Strabo did as well. The ancient writer Crantor took the other side, and so Atlantis believers of subsequent eras tend to quote him as ancient confirmation of Atlantis. His view, however, is certainly the minority opinion from antiquity.

The Lost City of Atlantis: The Atlantis of Early Modern Europe

The discovery of the New World in the late 15th and 16th centuries revived interest in Atlantis. As Fritze notes, “According to the medieval worldview, which was a mixture of Judeo-Christian and Graeco-Roman concepts, there were three continents: Africa, Asia, and Europe. These three continents were inhabited by the descendants of Shem, Ham, and Japheth, the sons of Noah. All humans could trace their ancestry back to Adam, the first man. . . . The discovery of the Americas upset all of these cosmographic assumptions. South and North America were two continents not envisioned in the medieval worldview and were inhabited by humans who possessed no apparent connection to any of the sons of Noah or to Adam. . . . During the 16th and 17th centuries, many theories were put forward to explain the origins of the Native Americans and the place of the Americans in the history of geography. Some writers turned to the concept of Atlantis and Atlanteans for an explanation (Fritze, 29-30).

There were two variations of an Atlantean explanation for the newly discovered Americas: the Atlantean refugee hypothesis and the idea that the Americas were themselves surviving vestiges of the continent of Atlantis. The latter was the point of departure for Sir Francis Bacon’s (1561-1626) concept of Atlantis in America, popularized in his unfinished but published (1610) book, New Atlantis. Though its details were entirely fabricated, the American Atlantis theory endured for more than two hundred years. The thesis dominated the study of Atlantis well into the 19th century. (Fritze, 30-34)

The Lost City of Atlantis: The Atlantis of Ignatius Donnelly

Without question the most popular book on Atlantis ever written is Ignatius Donnelly’s Atlantis: The Antediluvian World (1882). Born in Philadelphia, Donnelly tried and failed in business, politics, and farming before achieving success as a writer. Fritze observes:

While the scholarly underpinnings of [Donnelly’s] book are clearly inadequate and erroneous by the standards of present-day knowledge, in 1882 Atlantis represented a reasonable albeit unorthodox speculation about the events of the distant past. . . . Donnelly lived in an era before the advent of Alfred L. Wegener’s theory of continental drift, which was itself initially laughed at, and marginalized Geologists of Donnelly’s time postulated the existence of all sorts of lost continents and extinct geographies. In the 1880s, German biologist Ernst Haeckel and Austrian paleontologists Melchior Neumayor theorized about a land bridge connecting South Africa and India. The land bridge was given the name Lemuria by the English zoologist Philip Sclater. Lemuria would eventually be extended into the Pacific Ocean and become a Pacific version of Atlantis. This lost continent of the Pacific quickly attracted the attention of pseudo-historians and occultists who sometimes call it Mu instead of Lemuria. (Fritze, 37)

Donnelly also drew on the work of geologist Alexander Winchell, a leading geologist of 19th century America who sought to harmonize Christian doctrine with Darwin’s theory of evolution. Donnelly also drew on the work of 19th century leaders in archaeology and linguistics. Unfortunately, the material on which he drew in all these areas has not held up in light of advances in all these disciplines in the last 150 years.

The Lost City of Atlantis: The Atlantis of Theosophists and Spiritualists

Unsurprisingly, the mystery of Atlantis and the work of writers like Donnelly became grist for the mills of occultist writers like the prolific theosophist Helena Petrovna Blavatsky (1831-1891). Interestingly enough, Blavatsky’s two-volume Isis Unveiled (1881) mentions Atlantis only four times, basically to comment on the material in Plato. Her later two-volume tome, The Secret Doctrine (1888), is an entirely different story. A new vision of Atlantis in this later work became central to Blavatsky’s strange speculations about the evolution of the cosmos and humanity. The Atlanteans became Blavatsky’s fourth “root race,” arising 850,000 years ago. Blavatsky’s material was channeled during trances or drawn from the allegedly secret Book of Dzyan, composed in the lost language of Senzar. The reality of this book and this language has never been established.

Blavatsky’s ideas quickly filtered down to other occult movements fixated on lost history and theories about racial evolution and purity. Anthrosophy (Rudolf Steiner), Rosicrucianism, and occult Freemasonry all imbibed Blavatsky’s root races approach and Atlantean “lost knowledge” in their own pursuit of alternative history. Blavatsky’s content has deep roots in ancient alien “connections” to Atlantis, rogue archaeological speculations about Old World cultural diffusion to the Americas, and “lost tribe” speculative explanations for Native Americans or cultural accomplishments (e.g., mound building) allegedly beyond Native American knowledge and ability.

Summary

The mountain of speculation that has been piled atop Plato’s comments about Atlantis is truly startling. In our day, any submerged object that looks like the product of human hands must be Atlantis. It matters not that much of the speculation centers on places of which Plato had no geographical knowledge. It also matters not that the scientific argumentation upon which Atlantean ideas were based from the 16th through the 19th centuries is completely passé, having long been shown to be erroneous or incomplete. The romance of the idea of a lost city or continent simply outweighs that reality.

Resources:

Kenneth Fitzpatrick Matthews, “An Underwater City West of Cuba,” Bad Archaeology Blog (Oct 28, 2012)

C. Gill, “Plato’s Atlantis Story and the Birth of Fiction,” Philosophy and Literature, 3 (1979): 64–78

Ronald H. Fritze, Invented Knowledge: False History, Fake Science, and Pseudo-religions (London: Reaktion Books, 2009)

Paul Jordan, The Atlantis Syndrome (Sutton Publishing, 2001)

K. A. Morgan, "Designer History: Plato's Atlantis Story and Fourth-Century Ideology," Journal of Hellenic Studies 118 (1998): 101-118

Richard Ellis, Imagining Atlantis (Knopf, 1998)

Stavros P. Papamarinopoulos, “Atlantis in Homer and Other Authors Prior to Plato,” in Science and Technology in Homeric Epics (History of Mechanism and Machine Science; Springer, 2008): 469-508

What is your response?